Field trip to Hamilton Wetlands

On October 5, 2019 Environmental Forum of Marin (EFM) Masterclass 46 met at the Hamilton Community Center in Novato to learn about land management and conservation in Marin. We heard from the National Park Service/Golden Gate National Recreation Area, California State Parks, Marin County Parks, Marin Municipal Water District, and One Tam.

Nona Dennis started the day recounting her own curiosity in looking out her kitchen window and asking who owned Mount Tamalpais? She was surprised to find the land was managed by four agencies.

Nona took us back in time to the late 1800’s and early 1900’s when no public lands existed in Marin. Industry in Marin was primarily agriculture, logging, and military. Marin was geographically isolated from San Francisco and it was a time of big dams and water reservoirs. The land that is now Muir Woods was once slated for a reservoir to supply water to Sausalito. William Kent (1864-1928) acquired the land and in 1908 president Roosevelt accepted Muir Woods for the public under the antiquities act — redwood trees were considered antiquities. In 1928 William Kent donated the Steep Ravine land which became the foundation for Mount Tamalpais State Park.

On May 27, 1937 the Golden Gate Bridge opened, connecting Marin to San Francisco. Marin quickly became a popular tourist destination which prompted conservationist Carolyn Livermore to map Marin County and make recommendations for open space. She advocated successfully for Stinson Beach and Drakes Beach as the first Marin County parks, followed by Hearts Desire State Park on Tomales Bay, Samuel P. Taylor State Park, Angel Island, Olompali, China Camp State Park, Point Reyes National Seashore, and the Marin Headlands. The highest hill on Angel Island is named in her honor, Mount Carolyn Livermore.

Today, 85% of Marin is green space, preserved for agriculture or parks.

Marin County Parks

Mischon Martin, Chief of Natural Resources & Science at Marin County Parks presented on balancing stewardship and wildfire risk reduction. Marin County Parks manages 16,000 acres in 34 open space preserves.

What’s the difference between parks and open spaces? Parks are built spaces and may include food concessions, swimming pools, exercise equipment, etc. Open spaces are wild lands.

In 2012, Measure A provided a ¼ cent sales tax which allowed her to hire staff and to partner with other organizations including the Marin Agricultural Land Trust (MALT). It was a game changer which has provided the resources needed to effectively manage the lands.

Marin County Parks manages 250 miles of fire road and trails and is responsible for managing fire risk. It’s a huge amount of effort to clear plant growth to prevent the spread of wildfires, and to manage invasive species. They have to be strategic about how to focus their efforts to manage so much space. They have experimented with many methods including using goats to graze the land. Time of year is a critical factor, particularly for managing invasive weeds which should be removed before they spread their seeds.

Marin county has 107 native plant communities and 37 special status plants. Marin County Parks partners with other organizations on community science projects such as “bioblitzes” — inventories of the flora and fauna of an area, or cataloging photos taken by motion-sensor cameras to better understand wildlife patterns.

Check out the Marin County Parks events calendar for many FREE hikes and outdoors events throughout Marin. I can personally attest to how much I’ve enjoyed these events and how much I’ve learned. One of my favorites is the annual hike at Bull Point Trail in Point Reyes in July to observe rare flowers and butterflies.

California State Parks

Cyndy Shafer, Senior Environmental Scientist with California State Parks shared a history of the parks and the early environmental crusaders who brought them into existence. The State Parks manage 30,000 acres in the Bay Area, 14,000 acres of which is in Marin county. In total, California has 280 state parks that cover 1.6 million acres and nearly a third of the coastline. Parks funding comes from the State general fund and other sources such as bonds and entrance fees.

It all began with president Abraham Lincoln signing the grant on June 30, 1864 to make Yosemite the first state park. The federal government took over the park in 1906 when massive tourism began to have serious negative impacts on the park. The Sempervirens Club formed in 1900 to protect the old growth Redwoods of the Santa Cruz mountains from logging, and created the next park, Big Basin Redwoods State Park.

When you are a land manager, succession management is about controlling plants that would otherwise takeover, such as Coyote Brush replacing grasslands, and Douglas Firs crowding out Oak woodlands. In addition to managing plant communities, the parks restore physical processes such as converting old roads that are interrupting natural watershed flows to better planned trails. An example is the Dias Ridge Road to Trail project.

Like the Marin County Parks, they work with One Tam to collect scientific data and do monitoring on project such as the wildlife picture index, bat monitoring, and inventories of pollinators, spotted owls, salmon, seeps and springs.

2011 was a key moment in the California State Parks. Seventy of their 278 parks were slated to close due to budget cuts. In response park leadership undertook a Parks Forward Initiative and drafted a new vision for California State Parks. In 2015, the Department of Parks and Recreation created a Transformation Team dedicated to making a reinvigorated California State Park System a reality. Read the California Department of Parks and Recreation’s final report from May 2017 that outlines their plan and other reports from the project. One of the four strategic goals was to create new paths to leadership for staff which brought in new thinking (and many more women in leadership!)

Cyndy advised the Masterclass members to be advocates for sustainable access as well as conservation. Bring people to the park. The more they know about these places, the more they will care and want to take care of them.

Marin Municipal Water District

Shaun Horne, Watershed Resources Manager at the Marin Municipal Water District (MMWD) joined us. As the other guests had done before him, he had kind words for EFM and the masterclass. He believes a range of perspectives will bring new thinking to solve climate challenges. The cost of climate change far exceeds the funds available to land managers.

MMWD manages 7 reservoirs and 7 dams in Marin. As a result of damming, 55% of water is not available for streams and the critters that live in the streams such as the giant salamander, newts, California Red-legged frog, and salmon. It’s important to prolong the water yield - the time the water stays in the land before seeping into the streams. This supports the 900 plants and 400 species of vertebrates that live in the Mt. Tam area which is part of the UNESCO Golden Gate Biosphere reserve.

Some notable water stats

California uses one and a half times its size in water every year!

In California, 60% of water comes from the Sierra and 40% from the Colorado basin

2000 agencies deal with water in California!

For the watershed the MMWD manages, 16% is protected land, 51% has some protection, and 33% is private land. This makes it challenging to protect the watershed.

Average rainfall in Marin is 52 inches annually

National Park Service/Golden Gate National Recreation Area (GGNRA)

Brian Aviles is Chief of Planning and Environmental Programs for the Golden Gate National Recreation Area (GGNRA), which is part of the National Park Service (NPS). Among other duties, his staff of 16 manages remediation and hazardous materials of former military sites — lead paint is a big issue.

Preservation for 77 generations

Brian explained the NPS must take the long view on preservation. They must preserve our national parks and monuments for not just seven generations but for seventy-seven generations.

In the 1930’s the NPS started managing historic sites such as Gettysburg in addition to parks. By the 1960’s the condition of parks was poor due to lack of funds caused by the depression and the cost of world war II. Mission 66 brought improvements to the parks in the 1960’s. In the 1970’s congress passed many acts that contributed to conservation including the Wilderness Act, Clean Water Act, National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). The Redwood Act in 1978 established that conservation — not access, was the guiding principle for parks.

The National Park Service has one set of policies that apply to all parks. In 2006, NPS updated their management policy. The legislature describes why and how each park is established. In recent years, executive directives have been highly prescriptive about the maximum length of reports and the time in which they must be created.

Strategic planning

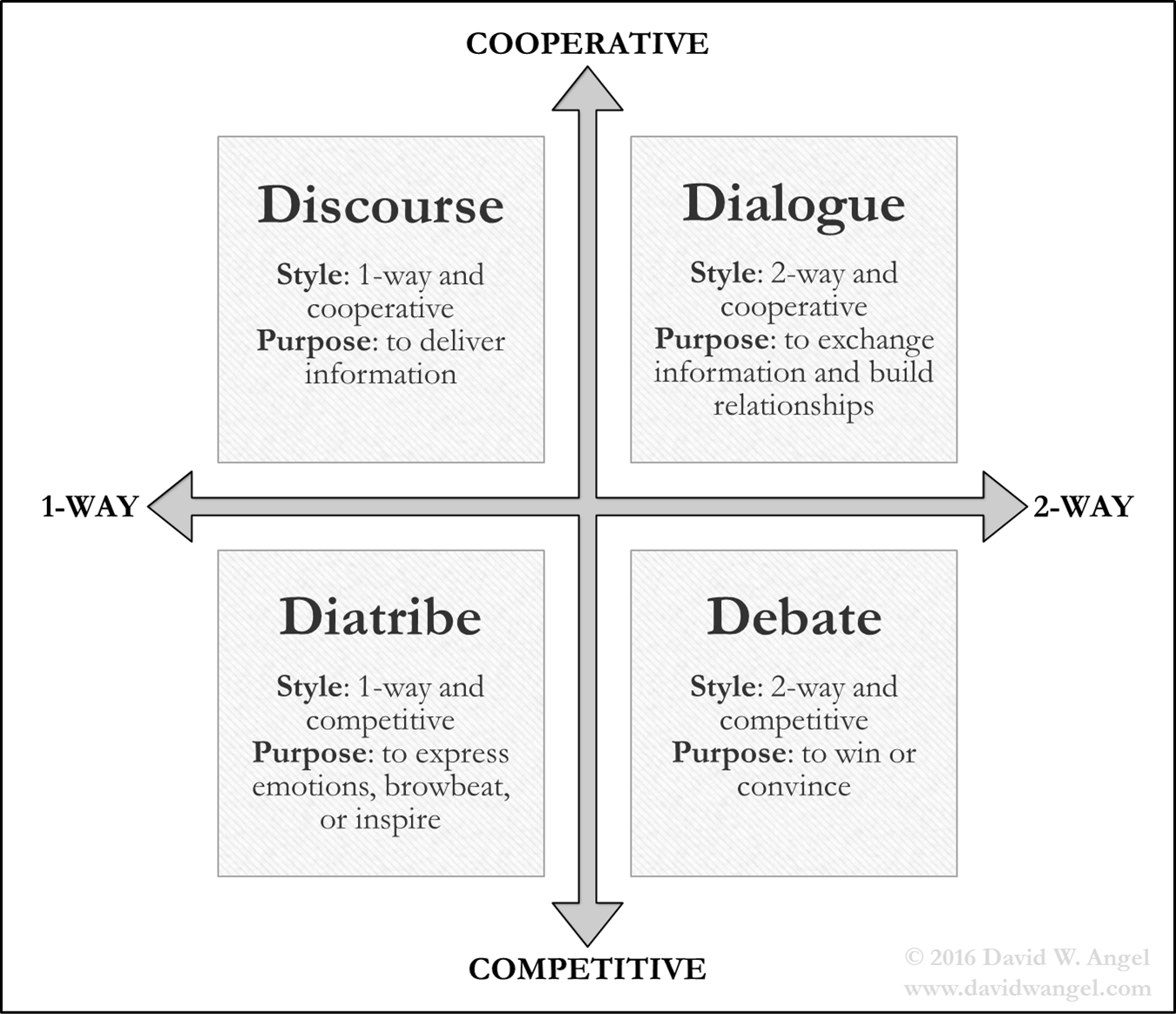

GGNRA is working on five initiatives from their 2016-20 strategic plan. Brian shared an interesting 4-square chart showing the different styles and their purpose in discussion. Read this article that describes these four types of conversation and when to use them.

One Tam

Sharon Farrell started as a volunteer and is now the manager of collaborative partnerships for One Tam, a non-profit organization that brings together all the agencies who contribute to conservation and management of Mt. Tamalpais. She is Executive Vice President of Projects, Stewardship & Science at Golden Gate Parks Conservancy. Sharon and her team lead the organization's project design and delivery, conservation initiatives, community science, restoration, and stewardship programs. One Tam’s tagline is “One Mountain, One Vision, One Tam”. One Tam believes working together is the best way to achieve landscape-scale stewardship of Mt. Tam.

Biodiversity

Mt. Tam has a wide range of plant communities from serpentine grasslands to conifer forests to wetlands, including many rare plants only found on Mt. Tam such as Mount Tamalpais Thistle (Cirsium hydrophilum var. vaseyi) and Mount Tamalpais Manzanita (Arctostaphylos montana ssp. montana).

Measuring the health of Mt. Tam

One Tam has aggregated 40 years of data from partnering agencies and used it to produce 25 key ecological indicators that measure the health Mt. Tam. They are aiming to add another 10 indicators. Currently, the overall health of Mt. Tam is “Fair”. Read the 2016 report Measuring the Health of a Mountain or learn more about the peak health of Mt. Tam and status of specific species. These clear and engaging indicators help people to see themselves as part of the solution for a healthier Mt. Tam.

Monitoring and community science

Selected projects One Tam is working on with partners:

The Wildlife Picture Index is the largest array of wildlife cameras in the United States. The goal is to study wildlife on public lands around Mt. Tam.

Bat monitoring for white nose bat syndrome. Working with GGNRA and Point Reyes National Seashore and others.

Large scale inventories and monitoring that provide a snapshot in time for a broad area to understand what’s happening and to do collaborative regional planning. This holistic approach is better than piecing together micro studies done at different times.

Stewardship and partnership are the new paradigms

Stewardship is as important as protection. Stewardship is taking care of the land - picking up your trash, and avoiding walking on sensitive areas off trail. Working together, agencies and the community can design better solutions to care for our lands and enjoy them. Along with stewardship, One Tam has shown that partnership can make a greater impact than working alone.

I greatly admire the idea of One Tam and the incredible work they are doing. Moreover, their ability to tell their story in a way that is engaging and inspires action is exciting and makes me want to join their efforts.

Hamilton Wetland Restoration

Our final speaker of the day was Ed Keller from the environmental section of the US Army Corps of Engineers. He described the incredible effort that went into restoring Hamilton Air Field to wetlands over a number of years, concluding five years ago in 2014.

Two endangered species make the Hamilton wetlands their home, the Salt Marsh Harvest Mouse (Reithrodontomys raviventris) and the Ridgway's Rail (Rallus obsoletus).

History

The Swamp Land Act of 1850 led to farmers claiming wetlands and diking them for agriculture. The other industry that claimed wetlands was salt production which was particularly active in South San Francisco. In the 1930’s the air force was looking for a replacement field to Crissy Field because it was in the flight path of the new Golden Gate Bridge.

Restoration

The project was the largest wetland restoration west of the Mississippi. It involved piping dredge materials from miles offshore to fill in land that had settled. The runway was left in place and is now eight feet under water with the exception of two pieces that were removed to make way for natural channels. These tidal wetlands are very fine grain silt and sand that doesn’t drain well. This meant the Army Corps was able to excavate small areas of fuel contamination easily by removing only seven feet of the silt. They had to set up a power generator to pump water and silt and became the biggest power users in Marin during the project. The Army Corps is required to do monitoring of the plants and wildlife for 13 years following the restoration. Ed led us on a walk and we admired the restoration work from several vantage points including above in the oak-filled hills and from the water’s edge.

Native plant nursery at Hamilton

We visited the native plant nursery that is raising plants for the wetlands. The nursery had a terrarium with an example of carbon sequestration.

Housing built on the marsh

I was surprised to see new housing developments on the edge of the marsh in what appears to be a flood plain. New levees were built to keep out the water. It made me wonder if the land developers paid for the levees and will continue to pay to maintain them or is that up to taxpayers? Perhaps looks are deceiving and this is indeed sensible housing development, but at a time when sea level is rising and we are moving development away from the flood zone, this waterfront development on the marsh had me scratching my head.